A New Approach to Promoting Flow in the Workplace

Today’s leaders face an insurmountable challenge of retaining high-quality employees. Not only are volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) situations arising, the workforce is embarking on a generational shift with significant implications for the effectiveness of more traditional and transactional leadership styles. When observing the sustainable careers of professional musicians, some individuals have careers span more than a half-century. Anne Miller marked a 71-year anniversary performing with the Red Hill Sinfonia last year. This phenomenon leads to the question, why and how? Simply stated, musicians spend their entire lives looking to enter the Flow state.

Whether the reason being of their own volition or for the satisfaction of optimal group work, the flow of musicians deserves a closer look at understanding how leaders may face the problems of VUCA and retention of younger employees. Music conductors have shown the ability to adapt in complex situations, addressing individual and group needs in seemingly simultaneous ways (Meals, 2020; Sutherland & Cartwright, 2022; Sutherland & Southcott, 2021).

Using a quantitative methodology and correlational design, the beginnings of empirical evidence suggest that the combination of active listening and time management used by music conductors has a high statistically significant relationship in promoting group flow (Ames, 2024). Using secondary gameplayer data from the leadership game FLIGBY, a quantitative correlational design was employed. The data from 8,346 millennial managers was used in the study. RQ1 sought to examine the relationship between active listening and corporate atmosphere (group flow score in FLIGBY). RQ2 examined the existence of a significant correlation between time management and the corporate atmosphere. These same characteristics are anecdotally shown in several accounts of music conductors (Krause, 2015; Talgam, 2015).

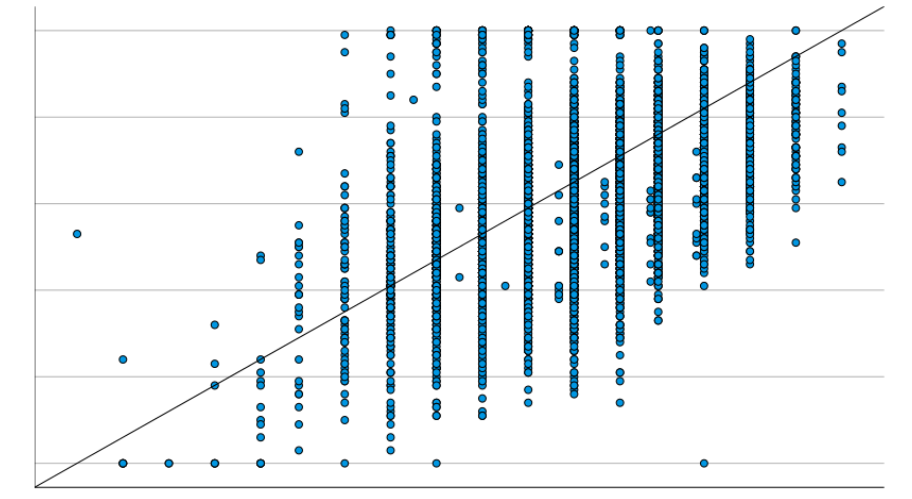

You can see in Figure 1 that there is a moderate statistically significant relationship between active listening and corporate atmosphere.

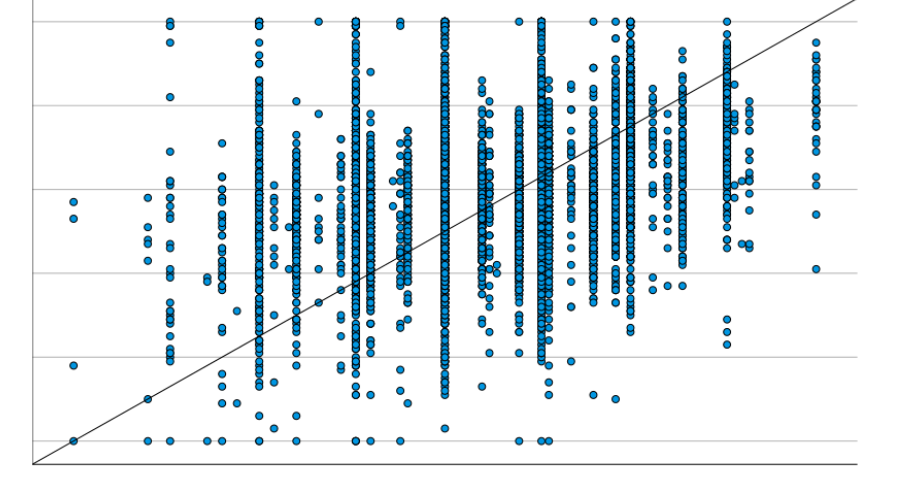

Figure 2 shows a slightly weaker but moderate relationship between time management and corporate atmosphere.

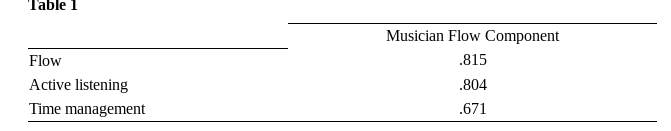

The most interesting part of the findings was found in a third RQ and suggests that a higher statistically significant relationship is created with the combination of active listening and time management using a principal component analysis (Ames, 2024). This suggests that the component used by conductors to increase the autonomy and creativity of professional orchestras can have a great impact on enabling group Flow.

Understanding one another better is made possible by listening. When done properly, active listening has the power to transform businesses and foster better teamwork among employees. Leadership training in time management, specifically how to read individuals, discern what they need and value, how much time to communicate with them, and how much time they need questions answered within can help increase flow state opportunities (Almeida & Buzady, 2022; Marer et al., 2016).

Data provides evidence for the development of flow leadership training programs in varying organizational fields. The elements of active listening and time management are crucial to understanding communication trends, and the timeliness of communication, and can help to develop more effective communication evaluation models. Teachers and leaders in business organizations can create environments of flow opportunities utilizing these skills.

Let the long careers of professional musicians show how Flow can create a meaningful livelihood out of group work. Active listening and time management could help leaders retain more employees by creating more frequent flow opportunities. As this component is more widely studied may it show a possible style that allows leaders to be better equipped for VUCA.

A guest contribution by Corey Ames, Ed.D.

Adjunct Professor at VanderCook College of Music in Chicago, IL. https://www.vandercook.edu/

Educational Doctorate at the American College of Education https://ace.edu/

References

Ames, C. (2024). Conducting Flow: A Quantitative Correlational Study of Music Conductor Leadership Traits in Millennial Business Managers [Doctoral dissertation, American College of Education]. forthcoming see here

Krause, D. E. (2015). Four types of leadership and orchestra quality. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 25(4), 431–447. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21132

Meals, C. D. (2020). The question of lag: An exploration of the relationship between conductor gesture and sonic response in instrumental ensembles. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 573030. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.573030

Sutherland, A., & Cartwright, P. A. (2022). Working together: Implications of leadership style for the music ensemble. International Journal of Music Education, 40(4), 613–627 https://doi.org/10.1177/02557614221084310

Sutherland, A. T., & Southcott, J. (2021). Fluctuating emotions and motivation: Five stages of the rehearsal and performance process. International Journal of Music Education, 39(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761420963984

Talgam, I. (2015). The ignorant maestro: How great leaders inspire unpredictable brilliance Portfolio.